An Incomplete Introduction to Blockchain Part-1

Hashing algorithms, Immutable ledgers, Distributed P2P networks

@Nihal Puram, Undergraduate, Indian Institute of Technology Madras

It’s a common concept among blockchain developers and was originally coined by the founder of ethereum, Vitalik Buterin. The blockchain trilemma is a set of three properties namely decentralization, security and scalability. The problems encountered by developers usually leads to a sacrifice in any one of the three aspects. This trade-off is visible in almost every modern blockchain. In order to achieve a perfect blockchain, it should have the following properties

Achieving universal mass scalability opens countless doors into the future. A lot of things that we take for granted in the modern world could be revolutionized. The technology could be used to maintain public records, land ownership, identity systems and not to mention transaction systems with fees lower than ever before. Achieving scalable blockchain allows us to do things never imaged before, such as a metaverse with products and real-estate ownership. More efficient governance and elections could be conducted through blockchains. The revolution could be described as similar to how the internet changed the business sphere or how e-commerce changed retail sales.

According to Cisco Systems, the global number of connected wearable devices is expected to reach 1,105 million by 2022, from 593 million in 2018. These mobile devices present in the market are capable of enough computational power as a 5-year-old computer. Some of these devices also have support for decentralized applications. Data centres around the world are implementing 400 Gbps network switches while 100 Gbps connections are quickly becoming the standard across the globe. With the advent of 5G and WiFi 6 on the horizon, it’s not too late before we see multi-gigabit wireless connectivity. This infrastructure is ideal for a future with mobile blockchain and decentralized applications.

The first and most major issue facing scalability in the blockchain is that of its transaction speed. Bitcoin can handle around 4-5 transactions per second and has a block time of 10 minutes, Ethereum can handle around 15 transactions per second and has a throughput of around 12-14 seconds. To be scalable and reach the heights of its potential blockchain technology must improve in this regard. Current payment technologies like Visa can process around 65,000 transactions per second.

Layer 2 blockchains were introduced to help increase the number of transactions by grouping together similar transactions so that they can be processed together. This although helps improve efficiency it’s still a long way off where we want to reach. Other limitations include skyrocketing transaction fees making common everyday transactions economically unviable. Block size and its ever-growing nature is also a major problem about which will be elaborated further along.

Consensus protocols are also a key factor in achieving scalability, as many nodes must be able to communicate with each other and be able to relay information across vast distances. Proof of work type algorithms that rely on heavy hash rate computation often tends to be slower as the same proofs require longer to verify. Proof of stake algorithms are much faster and do not require as much computational power.

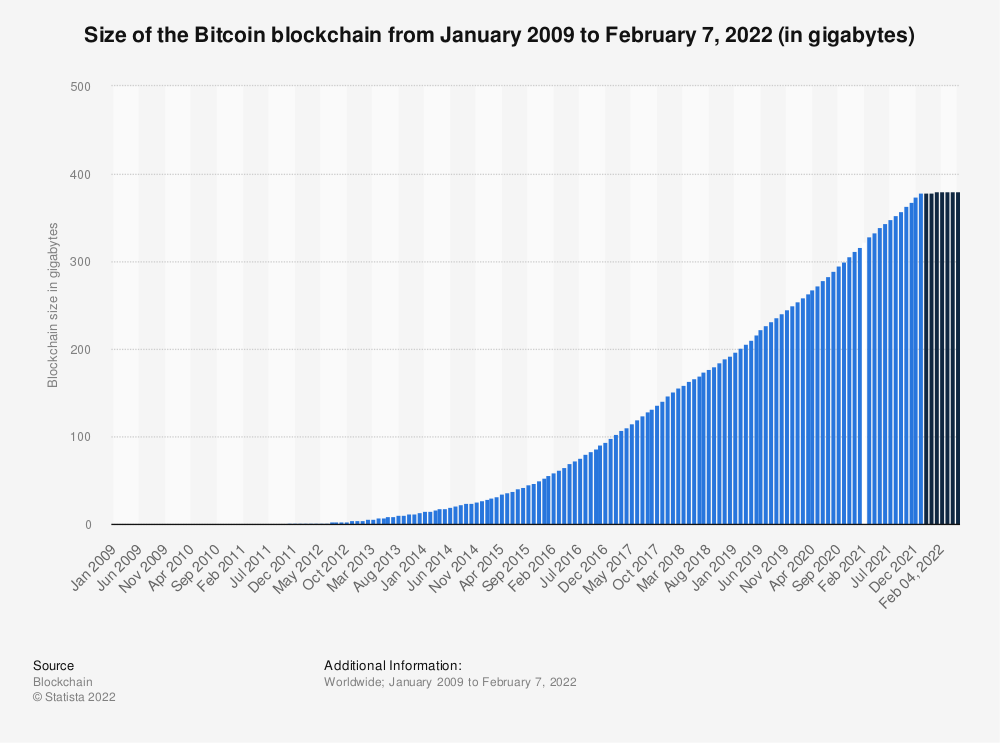

A blockchain is essentially a distributed ledger, and data is replayed across nodes and eventually appended to a block on the chain. As by design, this distributed ledger tends to grow as time passes. As of January 2022, Bitcoin has a size of almost 390 Giga-Bytes. This is up nearly 70 Giga-Bytes from last year. Ethereum has grown over 400 Giga-Bytes in the same timeframe.

In a truly decentralized system, nodes would have to keep complete copies of the entire blockchain. A constant supply of physical storage space has to be supplemented to nodes in order to be functional. This however on the mobile platform is very difficult to achieve. Even the majority of modern devices do not have the capability to store any of these large blockchains, and we can also expect the consumer to dedicate a small capacity of resources towards being part of the blockchain decentralization. The huge resource requirements of the existing blockchain technology severely discourage end-users participation in the decentralization process. Even if a newer more efficient blockchain takes over the fundamental problem of an ever-growing chain will never allow for full flexed scalability on the mobile platform.

Author of [] proposes a solution initially meant to fix blockchain bloat and creep. But have a fundamental flaw that fails to achieve scalability and mass adoption. They allow the nodes to naturally cull the oldest blocks at fixed intervals called epochs. The epoch length is determined by the consensus protocol. To avoid data loss the “unspent transaction outputs”(UTXO) will be rebroadcasted. The author named this procedure “automatic transaction rebroadcasting”(ATR) Any UTXO from the set that is to be dumped which can pay the rebroadcasting fee will be reincluded in the next block. These ATRs combine the older rebroadcasted UTXO with fresh newly spendable UTXO to form a new block.

To avoid data loss the “unspent transaction outputs”(UTXO) will be rebroadcasted. The author named this procedure “automatic transaction rebroadcasting”(ATR) Any UTXO from the set that is to be dumped which can pay the rebroadcasting fee will be reincluded in the next block. These ATRs combine the older rebroadcasted UTXO with fresh newly spendable UTXO to form a new block. After 2 epochs, the block producers may delete all block data, although the 32-byte header hash is retained to prove the connection with the original genesis block. In the original white paper, there is no mention of whether the lost data is recoverable.

The key as quoted by the author, is to ensure the “rebroadcasting fee” is a positive multiple of the average fee paid by new transactions over the previous epoch. This however is flawed in that any user is de-incentivized to hold on to the coin or token which is ideal to achieve scalability. Users over time will be charged just to store UTXO in their wallet which is unethical in my opinion. Users, in this case, would be forced to make ghost transactions to alternate wallets just to avoid the multiple average transaction fees of the ATR. This alone is a cause for concern preventing mass usage and scalability.

The author of [] makes the argument that this technique forces up the fees paid by older transactions and increases the amount of data pruned by the blockchain. The market reaches an equilibrium where old data is removed from the chain at the same pace that new data is added. But the author fails to account that the point of inflexion occurs when existing users are no longer willing to pay the higher transaction and rebroadcasting fees and would be pushed out of the system. This leads to a decentralized system meant for the population being unethically non-user friendly to the point that it would eventually lead to self-destruction and Saito’s downfall.

This approach does ensure that the space on the blockchain can be priced accurately even ass storage times approach infinity. Blockchain pruning does save money, and all forms of cheating disappear as nodes that do not store the whole blockchain are incapable of producing new blocks, as they do not know which payments must be rebroadcast. The Saito network also allows any node to create a block as long as it has enough “routing work”. “routing work” is defined as the amount required to be burned by the miner to produce the block. It depends on how quickly a block follows its predecessor. Consensus rules increase the value immediately after a block has been minted and gradually decreases until it reaches zero. Allowing any node to mint blocks is, in my opinion, an invitation to exploitative attacks. Although the author does discuss methods to dissipate the threat, this seems like an unnecessary inclusion. Although a “routing work” requirement may be a decent idea to increase the time between the minting of blocks, a simpler consensus like the proof of stake where randomized token-stakers are given the opportunity to mint blocks seems safer.

The Saito blockchain also dynamically may increase the amount of “routing work” needed for block production to keep block time constant as transaction volume grows. One can imagine how this may affect individual miners as the blockchain scales up. Miner’s will be forced to pay up more routing fees as the popularity of the chain increases.

As Saito tokens are burned as “routing work” to avoid a deflationary crash requires a blockchain to inject the tokens back into the system. But Saito does not simply give fees directly to the block producers as this may incentivize attackers to use the income from one block to mint the next. In my opinion, simply implementing a simpler consensus and not allowing anyone to mint, by adding a staking barrier would easily solve this problem.

This section contains ideas of improvement based on our discussion so far. To solve the problem of blockchain overgrowth or blockchain creep, we have a similar solution to Saito but with a few improvements.

As the block grows increasingly larger the older blocks would be removed from the chain. The genesis block will be shifted forward to create a new “temporary” genesis block. The unspent UTXO will be moved into the mempool and are required to be minted back into the blockchain in the next few blocks. This is an arbitrary value determined by the block time and use case. Sending unspent UTXO back into the mempool ensures there is no loss of value. There is no transaction or rebroadcasting fees for any UTXO moved from a defunct block into a new one. When a new block is created in the blockchain these older UTXOs are mixed in with the newer UTXOs. The process for Genesis Block Replacement may occur on a block threshold or a periodic basis based on the application. These older defunct blocks which would be removed would mostly contain old used UTXOs that would no longer be required in the active transaction space. This way Genesis Block Replacement improves space efficiency on the blockchain. I believe that technology would be a cornerstone towards a fully mobile node operated blockchain.

A natural question arises, who pays for the older UTXOs which are reintroduced into the system. The answer lies in some clever tokenomics. I have proposed that for every new transaction 50% of the transaction fee will go to a burn address, ie an address that is not controlled by anyone. This ensures there is a constant drain of currency in the system reducing inflation. Also, when an older UTXO is being reintroduced to a blockchain some of the newer UTXOs will not be required to burn their 50% share of the transaction fees. This allows enough incentive for the miner to introduce the older UTXO into the newly minted blocks. As a rule, no more than 49% of the transactions in a block can comprise older UTXOs. The miners will be rewarded a gift for successful minting of a block provided they satisfy all of the conditions according to the consensus protocol.

The consensus protocol is determined by use case, but theoretically, for faster transactions and improved scalability, we cannot use any traditional protocol. Bitcoin which uses proof of work has a block time of 10 min and a speed of 4.6 transactions per second. Ethereum which uses proof of stake protocol has a block time of 10-15 seconds and a speed of 15 transactions per second. These chains are simply too slow when compared to visa or MasterCard which can handle 65,000 transactions per second. In order to achieve a fully self-reliant, scalable mobile blockchain we need a faster more reliable consensus protocol.

Proof of history currently used by the Solana network is a potential consensus protocol. It uses a cryptographic clock and individually signs transactions at the nodes with hashes allowing the validators to check their validity as per the hashes. It is a high-frequency verifiable delay function. Solana is touted to support over 50,000 transactions per second with a block creation time of just 800ms.

There is still the problem of data loss when the older blocks are removed. This can be solved by using a double-ringed system. The rings in this context indicate authority and permissions. An example of the system could be as follows. The outer ring would contain general users using the shorter version of the chain implemented using genesis block replacement. Most of these nodes would be participating as mobile devices. The inner circle of nodes would not undergo the genesis block replacement and can store the complete blockchain. The incentives of inner nodes to hold the information is a subject of the application. This allows a historical link to verify debug or restore the blockchain provided it’s necessary.

In an ideal scalable blockchain network, the transactions have to be communicated across thousands of computers across the world. Especially if we are using mobile phones which rely on wireless connectivity. So, what happens when some of these nodes go offline or have bad connectivity.

In a blockchain network, we have more than a few nodes, losing a few nodes would be almost unnoticed by the system. This is by design as blockchains are massively distributed systems and are able to handle losing a few individual nodes. If you are a miner node on a POW chain you would lose the time you could have spent mining the next block. If you are on a POS chain you could lose your staking investment.

Any node that has been down for a while when coming back up will go into a “booting” state. The node will take time to catch up to the system and is completely determined by the number of transactions/blocks it has to verify. This bottleneck is usually resolved by the computational power of the node. If a blockchain using the genesis block replacement is used this process is faster as the amount of data transferred is much smaller.

The main motivation of my idea of using Genesis Block Replacement (GBR) is to facilitate the creation of massive public identity verifications systems on a distributed blockchain. This is feasible because the data size of each individual is quite small and can be stored on a blockchain at a reasonable size. This project is meant to be public-funded and all the minting nodes are centres where users can add or update their information. This could be taken further by linking the public and private keys of individual users with their biometrics. This opens us to a world of possibilities. You could store real estate information on the blockchain linked to these biometric public keys. Individuals could be able to transact huge amounts of immovable assets with a click of a button. Elections could be held on the blockchain with a lot of transparency although implementing a foolproof biometrics system is still a challenge. There is no requirement for any public document to be carried in person when you can recall them from the chain using biometrics. Everything from your passport, driving licence and identity cards could be stored against your public ID.